Montana Master Naturalist homework is the best homework.

I said what I said.

Like a lot of folks, I suffer from plant blindness. It’s not that I can’t see them, it’s that I choose not to, and it’s a bummer, because native trees can tell you a lot about the soil/weather/fire conditions of a place.

Also, what doesn’t belong (because it’s invasive, or pretty in the landscape) can tell you about the relative health of the ecosystem and/or the values of the people who live in a place.

Chinese Thuja has distinctive cones — apparently it’s a member of the cypress family, but the only species in the genus Platycladus (binomial is Platycladus orientalis). Really not from around here, but apparently somewhat popular as a small landscape tree in my neighborhood.

The Towani pine (Pinus sabiniana, aka gray pine, ghost pine, foothill pine) is also very much not from around here. I was walking by a house in my neighborhood and saw the cone in one of their flower beds. I couldn’t find the tree that it came from and it was the only one I saw (is it a decoration?), so I took a photo and moved on. (The Picture This! app says this cone is very dry, and the tree it came from might be dead.) Very cool cone, though, right?

So anyway, I’m trying to change the plant blindness situation… it’s going to take a while.

(P.S. I only take cones that have fallen from trees that I can identify nearby, and only if I can reach them from the sidewalk or trail. You don’t have to worry about this crazy lady foraging for interesting seed-bearing structures in your yard or park.)

I’m working on a nature journal page of interesting cones, and these are my models… not bad. Add a Doug fir (another super common tree in the area, and a sugar pine cone (not from around here, but I have one on my mantle), and I’ll call it good.

Last week we talked about fungi and lichens… another couple of cans of worms that are huge and interesting, and that I now still know nothing about, but understand why people might find them endlessly fascinating.*

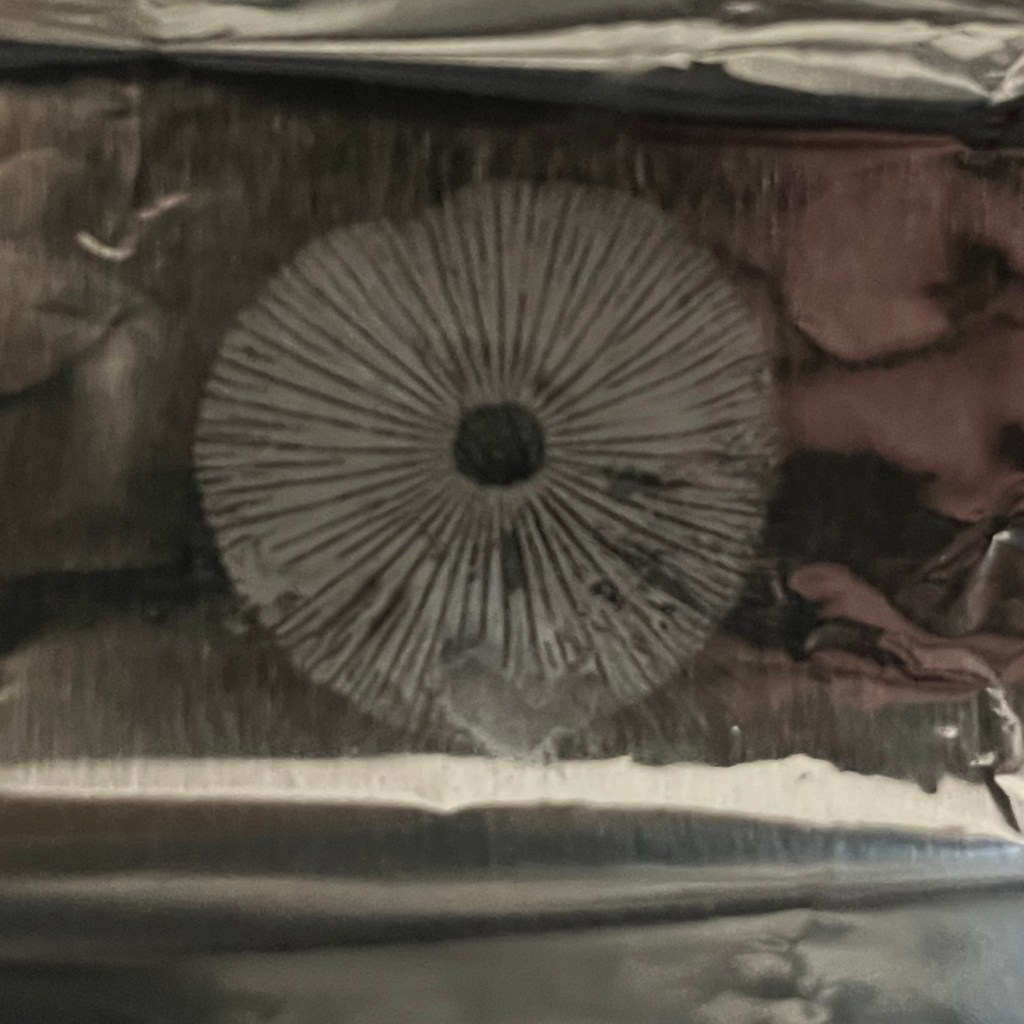

I have no idea what kind of mushroom this is. We’ve had a very dry couple of months here, so the places I would normally expect to see fungus… it’s either not happening, or the fruiting bodies are too mature to take a spore print. I was disappointed, because we actually have some shelf mushrooms (like Turkey Tail mushrooms, but I’m not going to hazard a guess that they actually are Turkey Tails) growing from willow stumps in one of the mews at the Outdoor Learning Center, but I couldn’t get a spore print from it.

This mushroom was foraged from a neighbor’s well hydrated hell strip. The substrate: grass and the soil that supports it. (I bet we had these when we had a fairy circle in our front yard many years ago.) I made the spore print on aluminum foil in case it turned out white (good call on my part), and was excited that I actually got something… this was my third attempt (with different mushrooms).

I’ll have to sit down with a key and see if I can figure out what kind of mushroom this is.

There are actually some really impressive fungi in my neighborhood, but I’m not going to forage my neighbor’s yard to get to them (at least not without asking first). These are growing from stumps in a yard that receives supplemental irrigation.

Here’s the main takeaway from our mushroom class: I’m not going to eat any mushrooms I forage without first consulting with a mycology expert… absolutely not. In fact, I will likely stick to cultivated varieties (or morels on a trusted restaurant’s menu).

Lichens are endlessly fascinating as well. Again, we’ve been pretty dry in an already dry summer region, so most of the lichens I’m seeing are of the crustose variety, low growing on rocks and bark. This little sample fell into my lap (or rather, in front of my feet), though, and I scooped it up to look at at home:

and a fruticose structure just above it.

I have to make some time to look at this through my loupe, because no doubt it is exquisite up close.

Are lichens organisms or ecosystems? That is the question. They’re made of fungi (sometimes more than one!), algae, and sometimes, cyanobacteria (what?!). Weird and wonderful.

And apparently, Montana is a hotbed of lichens and people who study them. (Go Montana!)

I love this stuff.

* I think this is the purpose of a master naturalist class — to be exposed to a lot that you won’t actually know much about at the end, but to create an understanding of why these subjects are important, introduce the idea that there are experts in all of these topics, and instill some empathy for people who are very excited about these subjects.