Today is MLK day. If you’re interested in reading one of King’s speeches, might I recommend his Give Us the Ballot speech, delivered at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom on May 17, 1957 (text courtesy of Stanford’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute). (H/T to Andrew Weissmann for the suggestion via his Substack newsletter.)

I’ve got a big semester coming up. Okay, so not any more intense than usual (I hope), but I think it will be both engaging and useful. Topics of courses this semester: data visualization, and instructional design. For the instructional design class, if the textbooks are any indication, we will be exploring information literacy, a topic most of us could learn a bit about and from.

I volunteer in an organization where I do a bit of community outreach — mostly with adults and families, but sometimes I get pressed into service to work with kids on field trips. I do raptor talks, or insect talks, or (very occasionally) nature journaling, so I work very much in the realm of things that can be observed first hand. That said, I hear a lot of assumptions about wildlife, in both kids (which I expect, because most of them are young enough to lack a lot of context), and their adults (which can be indicative that there’s a concerning lack of education in very basic biology and ecology), that are… incorrect… and sometimes dangerous, for both the animals and the people.

In the realm I work in, these assumptions tend to be variations on themes of “tameness” and training (which, again, is somewhat understandable, given that most of us don’t — and shouldn’t — have actual relationships with raptors), or human supremacy/dominance (in other words, because we exist, we have something to offer animals that we think they need, or we need to bring them to heel).

For most of us, our experience with animals is primarily with domesticated animals, like our pets. The understandable impulse is to apply our experience with our pets to other kinds of animals… which doesn’t work, and can be very dangerous, for everyone.

Take the ideas of tameness and training. These birds (who are unreleasable/cannot survive in the wild) are trainable, with consistency and a lot of practice, but they are not tame. They are not pets. Generally speaking, unless they are nesting or migrating, raptors are solitary. Stan is the possible exception, because Harris’s hawks live and hunt in small family groups in the wild. On the flip side of that, Stan, because he was raised primarily by people, turns into kind of a jerk when he’s looking for a girlfriend (he still has strong feet with sharp talons).

But Pants (rough-legged hawk) and Whoolio (Western screech owl)… definitely solitary — if they never saw any of us again, they would be fine. (I mean, they wouldn’t survive because their disabilities render them unable to hunt, but our absence wouldn’t leave them in any kind of emotional distress.) It’s difficult for us, as social animals, to understand that solitary animals do not need or want company; they are not lonely, and the presence of others often puts them at a competitive disadvantage.

And as for the other thing, the human supremacy… I’m not sure how to deal with that one, except to say that humans are bear-sized snacks, so if you are in bear habitat, you would do well to consider yourself a potential prey item and act accordingly. Interacting with moose, or bison, or Canada geese, is always a bad idea, because they don’t like us, and it would not matter if they did, because humans are predators and they do not want us in their spaces. A bison or moose that feels threatened could easily kill you and not think twice about it.

Even if we’re top of the food chain, the animals around us will do what they can to survive in our environment if we move into their habitat; coyote will do what they can to survive, including taking animals you may not want them to take. Same with owls. And raccoons (avoiding raccoons is tough; we live in a suburban area, and our dog treed two of them recently).

So yeah, having an opportunity to think about information literacy will be interesting. What is information literacy? How to we acquire it? How do we pass it on, in ways that people can ingest? If your thoughts about your interactions with animals are based primarily on vibes/your experiences with your pets, how can I introduce you to a way of thinking that’s more inclusive of wild animals and their habitats — in a way that is factual, and respectful/compassionate?

On another (very much related) front, I have to do some continuing education to maintain my Montana Master Naturalist certification. In past years, I’ve done nature journaling coursework, or seminars about ecology topics around the West. This year, I’m changing it up a little bit and working on introductions to topics that are more foundational, like ecology, climate change, and fire ecology (which, if — like me — you live in the Western US, is a topic you’re already probably more familiar with than you would like to be).

One of the reasons I love the internet is that you can learn just about anything. So, for ecology, I’m taking a Coursera Course: Introduction to Biology: Ecology (offered by Rice University).

I’m enjoying the content. It’s very basic, and the stakes are low. But it’s informative for a person like me, whose education has been mostly liberal-arts based, and who is interested in being exposed to a new and different topic.

I’m using this course to develop a little bit of foundational knowledge on the broad topic of ecology, and then using that foundation to inform some investigation into the topics of climate change, and fire ecology.

And hopefully, I’ll be able to bring some nature journaling into all of it.

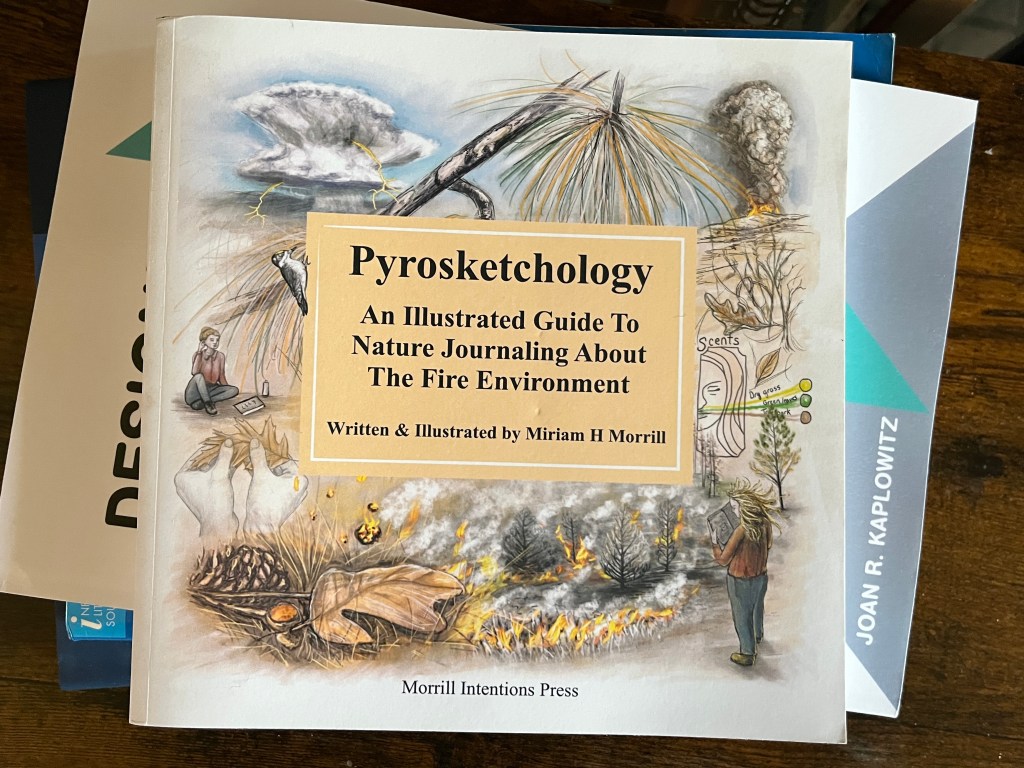

This looks to be an excellent book. I’m excited to delve into it while I learn more about fire ecology. (Bookshop.org link)

So, yeah, much to do this spring. I’m looking forward to it.

(Today will also include making a loaf of beer bread and some lentil soup for dinner.)